The old adage of a chicken in every pot and a car in every garage encapsulated what was considered an ideal American life: tranquil, economically viable and, most importantly, acquiescent and inconspicuous. citizens sought comfort during a transformative time in the country’s history.

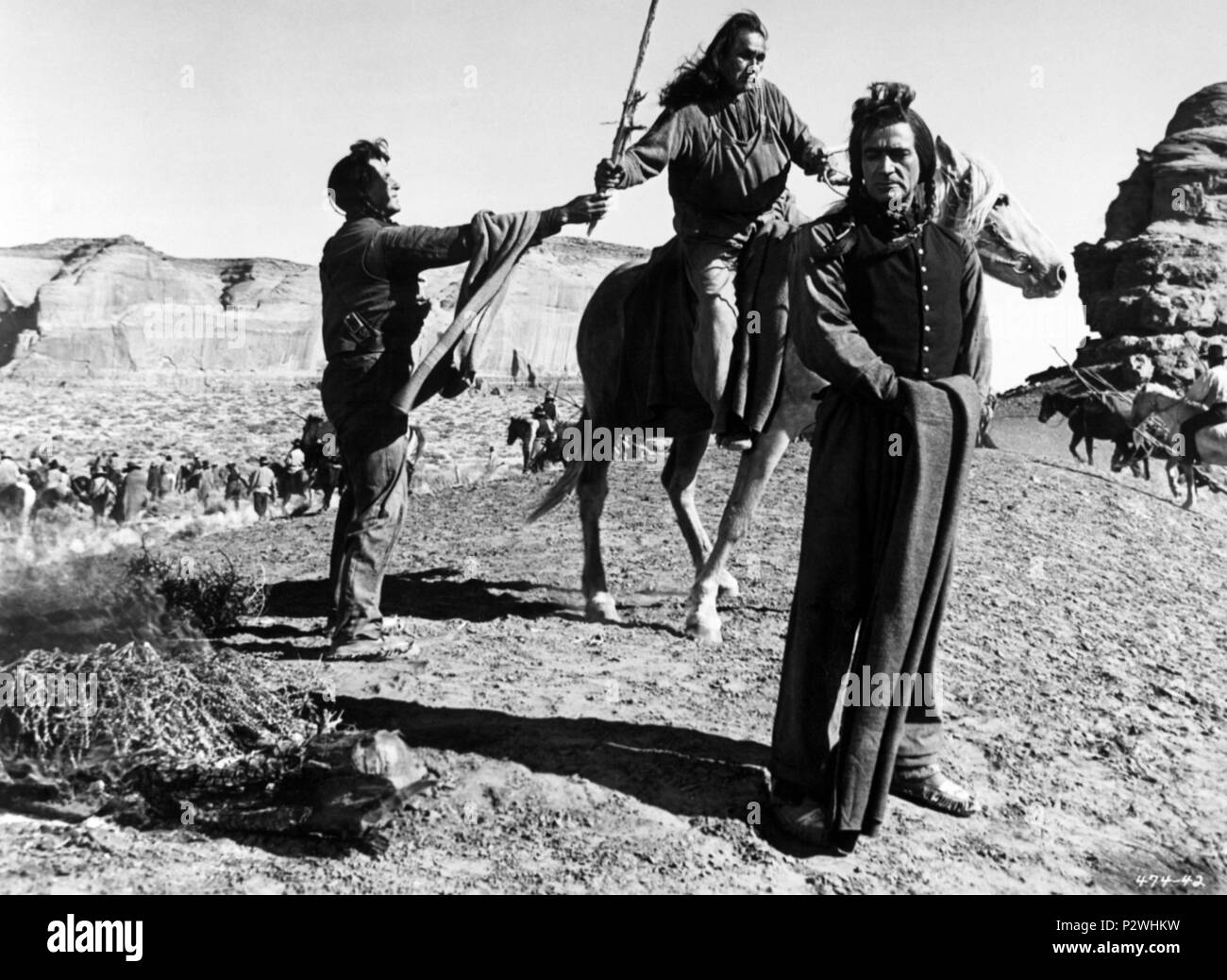

Such iconography can be found throughout Ford’s work, but it is essential to note just how the context shifts over time.įord’s post-WWII films tend to reflect the burgeoning American Dream, an ideal that came into being after U.S. Ford’s earlier Westerns possess something of a sunnier disposition, or are at the very least a kind of mirroring of the “Wild West” forever etched into the American consciousness: dusty trails, ten gallon hats, rolling tumbleweeds and, perhaps most prominently, the six-shooter pistol. Perhaps the more apt statement is “John Ford mastered the Western,” or even “John Ford created the Western.”įord made a number of notable films outside the genre, but in looking specifically at his Westerns, one is able to discern all they need to know about the director: his sense of humor, his moral and political values, his trademark visual and thematic idiosyncrasies. One of the few inarguable statements in all of cinema is, “John Ford made Westerns.” It’s inarguable in the sense that it’s patently true-like saying Preminger made noirs or Sirk made melodramas-but also in the sense that Ford seemed to embody the ethos of the genre.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)